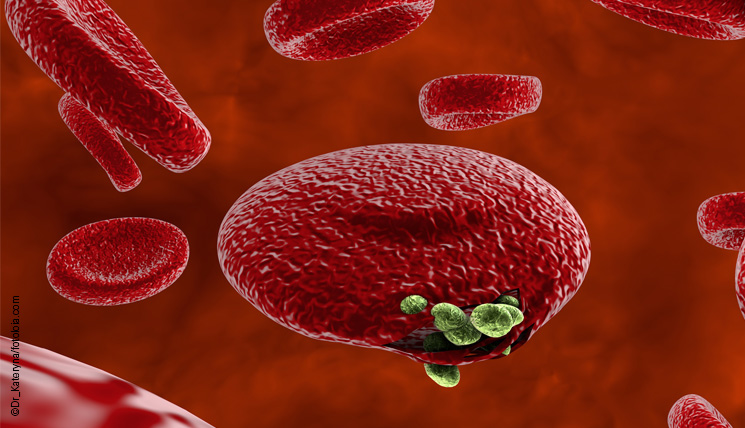

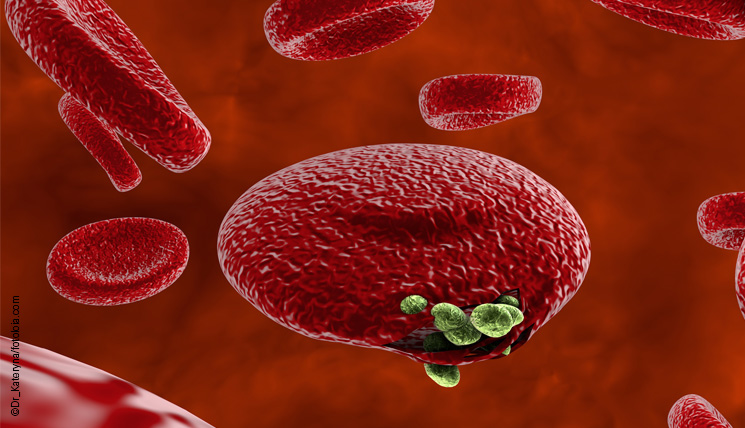

Malaria Eradication possible by 2050; Lancet study

A study published in the Lancet hints that the world may be able to eradicate malaria within the next 30 years. “Malaria, one of the most ancient and deadly diseases of humankind, can and should be eradicated before the middle of the 21st century,” reads the report.

A study published in the Lancet hints that the world may be able to eradicate malaria within the next 30 years. “Malaria, one of the most ancient and deadly diseases of humankind, can and should be eradicated before the middle of the 21st century,” reads the report.

The study found that more than half of the world’s countries are malaria-free today, encouraging discussions about completely eradicating the disease.

The report was compiled by a diverse range of experts including malariologists, biomedical scientists, economists, and health policy experts. The authors have used new modelling methods to predict how prevalent and intense malaria could be in 2030 and 2050. Their report concentrated on available evidence with the latest epidemiological and financial analyses and demonstrates that with the right tools, strategies, and sufficient funding, elimination of the disease is possible by 2050. The report also added that the communities plagued by malaria could choose to commit to a time-bound eradication goal with purpose, urgency, and dedication, instead of gradual efforts to reduce malaria, which comes with the constant threat of resurgence, and a steeping struggle against drug and insecticide resistance.

“For too long, malaria eradication has been a distant dream, but now we have evidence that malaria can and should be eradicated by 2050,” said Richard Feachem, Director of the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) in the US.

While global malaria incidence and death rates declined by 36 and 60 per cent respectively since 2000, the advancements are threatened by recent plateaus in global funding, together with a rise of malaria cases in 55 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

According to the authors, there are more than 200 million cases of malaria reported annually around the world claiming nearly 50,000 lives. Malaria continues to trap countries in cycles of inequity, with 85 per cent of global deaths reported in 2017 coming from 29 nations.

To achieve eradication within the timeline, the commission urges that specific and deliberate actions at country, regional and global levels must be taken with three ways to accelerate the decline in malaria cases worldwide.

The commission suggests that first, the world must manage and implement current malaria control programmes better with improved use of existing tools, what it calls the “software of eradication. Secondly, they highlight the need for better “hardware of eradication” with the development and supply of innovative tools that can overcome the biological hurdles in the eradication. The authors also say that malaria-endemic countries and donors must provide more funds for eradicating the disease.

Though the cost of ridding the world of the disease is unknown, the commission suggests that an annual increase of about USD two billion would accelerate the progress. From the simulations, the authors also report very high-levels of malaria control with the combined use of fast diagnostic tests, mosquito nets, indoor spraying of pesticides, and a combination therapy based on the anti-malarial drug Artemisinin. To achieve effective spraying of pesticides, the report suggests that a more sustainable approach, with greater to the local economy, is for the health ministries of endemic countries to contract with a local for-profit or not-for-profit entities.

Source: Times of India