Do Declining Covid-19 Numbers Suggest Pandemic Is Coming To An End In India?

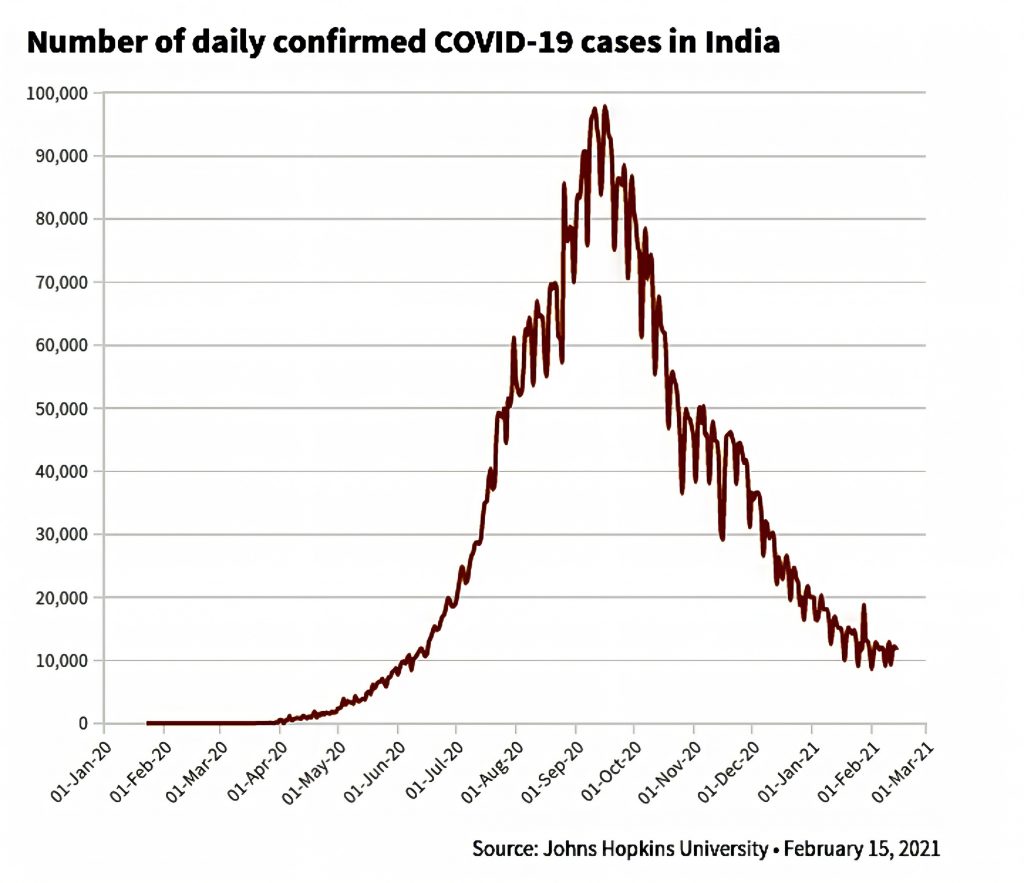

When the coronavirus pandemic took hold in India, there were fears it would sink the fragile health system of the world’s second-most populous country. But infections began to drop sharply in September, and now the country is reporting just about 11,000 new cases a day, compared with a peak of nearly 100,000.

The seven-day rolling average of daily deaths from the disease slid to below 100. More than half of India’s states were not reporting any Covid deaths and what’s more, Delhi, once an infection hotspot, did not record a single Covid death on Tuesday, for the first time in 10 months.

At a time when many other countries are battling second and third waves and alarming new variants of coronavirus, the drop in infections raises a tantalising prospect- Are we finally seeing a light at the end of India’s COVID-19 tunnel? It is but natural for the common man who’s been living in fear of the virus for over a year to wonder about the end of the pandemic. But what does this “end” even mean? Let’s look into it in detail.

So far, India has recorded more than 11 million infections – the second-highest in the world after the US. There have been over 150,000 reported deaths from the disease. The number of deaths per million people stands at 112, much lower than what has been reported in Europe or North America. Most pandemics typically rise and fall in a bell-shaped curve. India has been no exception.

With this, the strain on the country’s hospitals has also eased in recent weeks, giving some breathing space for the doctors and healthcare workers across the country who were burnt-out by the pandemic. When recorded cases crossed 9 million in November, official figures showed nearly 90 percent of all critical care beds with ventilators in New Delhi were full. On Thursday, only 12 percent of these beds were occupied.

With the world’s largest vaccine drive underway clubbed with a steady decline in the number of active and new cases over the last few months, the nation has eased the restrictions which were brought in as part of the Covid containment efforts. But is it the right move now?

Experts reminded that there have been multiple waves of the disease across the world and many countries saw a new wave at a time when they felt secure with the declining number of cases. The Brazilian city of Manaus, which at the end of last year, was being cited as an example of herd immunity leading to a drop in the number of cases, ran out of oxygen last week because of its healthcare being overwhelmed by the second wave.

We have to also keep in mind what has happened in countries like the UK and New Zealand. Many such countries had experienced a prolonged lull in the past, extending for several months, when very few cases were discovered. So much so, that a country like Spain opened up almost completely last year, before being forced to shut down again. What we have seen in these countries is the emergence of newer variants, newer mutants of the virus. This certainly shows that we need to be very cautious about easing all restrictions.

So why are cases dropping?

Some doctors and researchers are beginning to speculate that India’s crowded cities may be approaching the early stages of natural “herd immunity” — even before a vaccine is widely available — causing the spread of the pathogen to abruptly lose steam. “I am hopeful that the worst is over,” says Dr. Randeep Guleria, director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and a member of the government’s Covid-19 task force. “In certain areas, like large cities, we may have come close to achieving a good amount of immunity — if not herd immunity, close to it.”

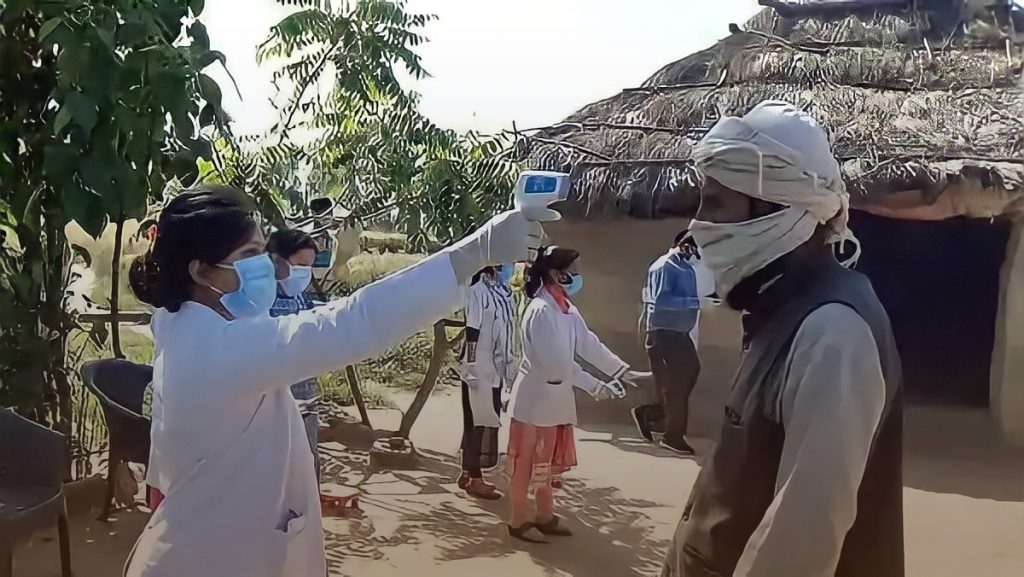

A nationwide screening for antibodies by the national health agencies estimated that about 270 million, or one in five Indians, had been infected by the virus before vaccinations started – far below the rate of 60-70 percent or higher that experts say might be the threshold for the coronavirus. However, the survey offered other insight into why India’s infections might be falling. It showed that more people had been infected in India’s cities than in its villages and that the virus was moving more slowly through the rural hinterland.

Another possibility is that many Indians are exposed to a variety of diseases throughout their lives – cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis, for instance, are prevalent – and this exposure can prime the body to mount a stronger, initial immune response to a new virus. “It is a combination of factors that gives the population immunity, but not this concept of herd immunity, which as I said is very nebulous,” said Dr. K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India.

The other explanation is that India has and continues to miss lots of cases, mainly because a large number of infected people have no symptoms at all or have a very mild infection.

Is the low death rate a mystery?

Coming to the mortality rate, researchers say that India’s overall Covid mortality rate has likely not been as high as many other regions. One reason for that could be the relative youth of the country’s population. Just 6.5 per cent of India’s population is over 65 years old, compared to one-fifth in Europe.

Scientists have also attributed lower fatalities to protective immunity, a vast rural populace with negligible links with cities, genetics, poor hygiene, and ample lung protecting protein. However, most scientists believe that many more Indians died of the infection than what the official figures reveal. India has a poor record of certifying deaths and a large number of people die at home.

Is the pandemic coming to an end?

Bloomberg has built the biggest database of Covid-19 shots given around the world, with more than 119 million doses administered worldwide. US science officials such as Anthony Fauci have suggested it will take 70% to 85% coverage of the population for things to return to normal. Based on this, the vaccine calculator shows that it will take the world as a whole seven years at the current pace for the COVID-19 pandemic to finally come to an end!

Coming to India, the rise of new variants has added another challenge to the nation’s efforts in flattening the curve. Scientists have already identified several variants of the coronavirus in India which includes 160 cases of the UK variant until the end of January. The ICMR had on Tuesday announced that the South African variant of coronavirus circulating in more than 44 countries has also entered India with four people having been detected with the strain. India has also reported one case of the Brazilian strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

If the mutants enter and they start rising in numbers, and particularly other susceptible sections of our population who have not been infected so far or have not been vaccinated so far get affected, then we can still have a sudden spike in the cases. And the curve which came down in the last few months can go up within no time.

One thing is very clear, even when the cases are coming down danger still lurks around the corner, and it’s no time to let down our guard. To relax our vigilance now – having reached so far and at such cost – is surely not an option we should consider.

Follow and connect with us on Twitter | Facebook | Instagram